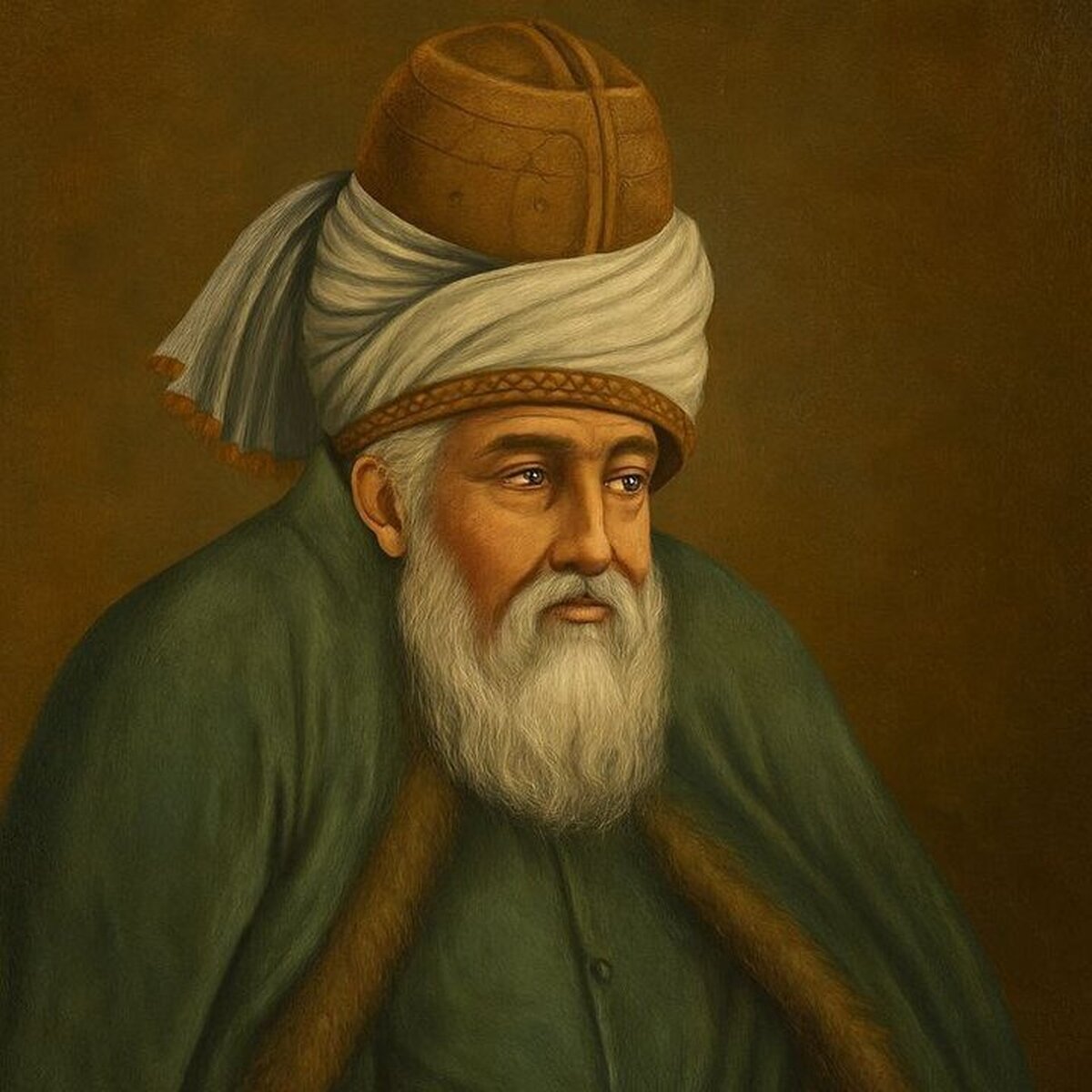

Rumi: The Persian Mystic Who Continues to Inspire the World

Tehran - BORNA - Few figures in world literature have left as deep and universal a mark as Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi, better known as Rumi or Mowlana. More than eight centuries after his birth, Rumi’s words continue to echo across continents, resonating with people of every language, faith, and background. For Iranians, he is one of the brightest stars of Persian culture; for the world, he has become a poet of the soul, a mystic whose message of love and transcendence remains as relevant today as it was in the 13th century.

Rumi was born on September 30, 1207, in the ancient city of Balkh, then part of the Persian cultural sphere, now within modern-day Afghanistan. His family, native speakers of Persian, fled political turmoil and Mongol invasions, eventually settling in Konya, a town in present-day Turkey that was at the time under the rule of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. From Balkh to Konya, Rumi carried the linguistic, cultural, and spiritual heritage of Persia, shaping his path as both scholar and poet.

The Iranian calendar marks the 8th of Mehr each year as a day of remembrance for Rumi. This commemoration reflects not only his status as one of Iran’s most celebrated poets but also his enduring role as a global cultural and spiritual icon. His works are studied in schools across Iran, quoted in music and art, and inscribed on the walls of cities—yet their influence extends far beyond Iran’s borders.

Early Education and Family Roots

Rumi’s father, Baha’ Walad, was a distinguished theologian and mystic, whose teachings left a lasting impression on his son. Under his father’s guidance, Rumi received a traditional education in Islamic sciences—Qur’anic exegesis, jurisprudence, theology, and philosophy. By the time of his father’s death, the young Rumi had already begun to emerge as a respected scholar and teacher in Konya.

But it was not dry scholasticism that would define Rumi’s destiny. Rather, it was the fusion of intellect and mysticism, inherited from his Persian roots and enriched by the turbulence of his age, that transformed him into a poet whose vision transcended religious dogma and cultural boundaries.

A Turning Point: Encounter with Shams of Tabriz

The most decisive event in Rumi’s life occurred on November 30, 1244, when he met Shams al-Din of Tabriz, an enigmatic dervish and spiritual wanderer. According to tradition, Shams posed a series of piercing questions to Rumi in the streets of Konya, questions that shattered his conventional world and ignited a spiritual revolution within him.

Though scholars debate whether their first meeting took place in Syria or Konya, what is undisputed is the profound effect of Shams on Rumi’s life and poetry. Shams became Rumi’s spiritual guide, companion, and muse. Their relationship—intense, mysterious, and transformative—gave birth to Rumi’s most celebrated lyrical collection, the Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi (The Collected Works of Shams of Tabriz), written in Persian and infused with ecstatic love and longing for the divine.

This friendship was not without controversy. Many of Rumi’s followers and even members of his household could not comprehend the depth of his attachment to Shams, leading to jealousy, tension, and eventually Shams’ disappearance—whether through exile or assassination remains unclear. Yet the grief of separation only deepened Rumi’s creativity, fueling some of his most powerful verses.

Major Works: Masnavi and Divan

Rumi’s literary legacy is monumental. His Masnavi-ye Ma’navi (Spiritual Couplets), a six-volume epic composed in Persian, is widely regarded as one of the greatest masterpieces of Islamic mysticism. Sometimes described as the “Qur’an in Persian,” the Masnavi combines parables, metaphors, and allegories to address profound questions of metaphysics, morality, and divine love. It guides the reader on a journey of the soul, from the bondage of the ego to the freedom of union with the Beloved.

Alongside the Masnavi, Rumi’s Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi contains thousands of lyrical ghazals and quatrains dedicated to Shams, pulsating with passion and spiritual ecstasy. His Fihi Ma Fihi (Discourses), Makatib (Letters), and lesser-known sermons further reveal his role as a teacher and guide. Together, these works form a body of literature that transcends time, language, and geography.

Universal Language of the Soul

What sets Rumi apart is not only the depth of his mystical insight but also his ability to articulate universal truths in simple yet profound metaphors. His verses often speak of love as the central force of existence—a love that begins with human relationships but ultimately points toward the divine. In Rumi’s world, the heart becomes the gateway to God, and every experience of joy, sorrow, loss, or desire is a step on the path toward spiritual awakening.

Centuries later, his words remain alive, offering guidance to seekers across cultures. From the East to the West, from mosques to churches to yoga studios, Rumi’s poetry continues to bridge divides, reminding humanity of the eternal quest for love, unity, and transcendence.

At the core of Rumi’s poetry lies a vision of life shaped by love, humility, and transformation. For him, love was not a sentimental feeling but the very essence of existence, the divine fire that animates all creation. He wrote of love as both earthly and divine, a force that first appears through human affection but ultimately leads the seeker to God.

In one of his oft-quoted lines, he declares: “Love is the bridge between you and everything.” This radical idea places love as the universal language of the soul—transcending nation, creed, and time.

The Call to Transcend the Ego

For Rumi, the greatest obstacle to divine union was the ego, or the false self. He described the ego as a cage, a veil, a thief that robs humanity of its true essence. His Masnavi is filled with allegories in which kings, beggars, lovers, and saints all symbolize the struggle against the ego.

The path of the mystic, he insisted, required shedding pride, arrogance, and worldly attachments. “Die before you die,” Rumi urges, calling for the death of the ego so that the true self—the soul—might awaken. In this sense, his teaching echoes the broader Sufi tradition while giving it an unmistakably Persian poetic intensity.

The Power of Metaphor

Rumi’s ability to render abstract ideas into vivid metaphors remains one of his greatest strengths. He speaks of the soul as a reed cut from the reed bed, producing a mournful song that yearns for reunion. This image opens the Masnavi and has become symbolic of humanity’s longing for the divine.

Elsewhere, he likens the ego to a cloud obscuring the sun, or to a prison keeping the heart from freedom. He employs images of birds flying, moths circling flames, wine cups spilling, and oceans without shores. These metaphors make his mystical philosophy accessible to ordinary readers, while at the same time offering infinite layers of meaning for scholars.

Love as Divine Union

While Rumi’s poems are often read as romantic verses, their true meaning is mystical. The beloved in his poetry is not simply a human partner but the Divine itself. The intoxication he describes is not from earthly wine but from the ecstasy of encountering God.

His verses about Shams of Tabriz are the clearest examples of this: Shams is at once his human companion and a mirror reflecting the divine light. Through Shams, Rumi experienced the annihilation of the self (fana) and the rebirth into divine unity (baqa).

This duality—seeing the divine in the human and the eternal in the fleeting—defines the unique beauty of his work. For this reason, his poems resonate not only with Muslims but with readers of all traditions, from Christians who see echoes of divine love in his words to Buddhists who recognize his call for selflessness.

Ethics and Humanism

Though Rumi was a mystic, he never abandoned the world of ethics, justice, and community. His poetry speaks constantly of compassion, fairness, and humility. He urged rulers to be just, scholars to be humble, and ordinary people to practice generosity.

The Masnavi is full of anecdotes illustrating moral lessons: a greedy man losing everything, a patient teacher guiding a stubborn student, a king learning humility before a beggar. These stories remind readers that true spirituality cannot be divorced from daily life.

Rumi thus bridges the gap between the mystical and the practical. His vision of divine love does not retreat into isolation but manifests in kindness toward neighbors, fairness in trade, and mercy for the weak.

Music, Dance, and the Path of Ecstasy

Rumi’s teachings also gave birth to the Mevlevi Order, whose whirling dervishes embody his belief in the union of body, mind, and spirit through dance and music. The act of spinning, with one hand pointed toward heaven and the other toward earth, symbolizes the mystic’s role as a conduit of divine love, receiving from above and giving to the world below.

For Rumi, poetry, music, and dance were not distractions but vehicles for reaching God. He argued that when words fail, rhythm and movement can lift the soul to ecstatic states of awareness. This fusion of art and spirituality continues to define his legacy in Turkey, Iran, and beyond.

A Timeless Spiritual Psychology

Modern readers often describe Rumi’s work as a form of spiritual psychology. His insights into fear, anger, jealousy, and pride remain startlingly relevant. He speaks of the restless human mind, forever chasing desires, and of the heart’s deeper longing for peace.

In contemporary terms, his poetry can be seen as a manual for inner healing:

He calls on people to confront their shadows, not deny them.

He insists that suffering can become a doorway to transformation.

He promises that every wound is a place where the light can enter.

Such messages explain why Rumi’s verses appear today in therapy sessions, mindfulness retreats, and interfaith gatherings. His timeless psychology speaks to the anxieties of modern life as powerfully as it did to the turmoil of the 13th century.

Rumi is celebrated worldwide, yet his deepest roots remain firmly planted in Iranian culture and history. Known affectionately as Mowlana (“Our Master”) in Iran, he stands as a pillar of Persian literature, alongside Ferdowsi, Saadi, and Hafez. Unlike many classical poets who are read mainly for their aesthetic brilliance, Rumi is studied not only for beauty but for spiritual guidance.

Rumi in Iran Today

Across Iran, Rumi’s words echo daily:

Verses from the Masnavi are printed on the walls of schools and mosques.

His poems appear in school textbooks, teaching young generations both Persian language and moral lessons.

His works are set to traditional Persian music, with singers drawing on his verses to create songs of longing, joy, and divine love.

Cultural festivals in Iran often dedicate special programs to his memory. The 8th of Mehr in the Iranian calendar is observed as Rumi Day, marking a national tribute to his enduring influence. Universities hold conferences, and cultural centers organize recitations and performances that connect classical poetry with contemporary issues.

Even in ordinary conversations, Iranians often invoke his words. When confronting hardship, one may quote: “Don’t get lost in your pain; know that one day your pain will become your cure.” Rumi’s voice remains a companion in both joy and sorrow, anchoring everyday life in a centuries-old poetic tradition.

The Persian Language as Rumi’s Vessel

Although Rumi lived much of his life in Konya (in present-day Turkey), his entire literary output was composed in Persian (Farsi). This fact underscores his belonging to the Persian literary world. His Persian is elegant yet accessible, combining mystical depth with lyrical simplicity.

Through Rumi, Persian became a global language of spirituality. His verses were later translated into Turkish, Urdu, Arabic, and many European languages, but the original Persian continues to carry a musicality and rhythm that translation often cannot replicate. For Iranians, reading Rumi in the original language provides not only literary pleasure but a profound sense of cultural continuity.

Influence on Iranian Arts and Philosophy

Rumi’s impact extends beyond poetry:

Visual Arts: Persian calligraphers often inscribe his couplets in mosques, palaces, and manuscripts. His words are not just read but visually celebrated.

Philosophy and Theology: Iranian scholars and clerics have drawn on his works to explain Sufi doctrines, ethics, and metaphysics. His interpretations of divine love and unity influence both academic debates and religious sermons.

Popular Culture: His metaphors—like the reed flute or the moth circling the flame—have entered everyday idioms. Painters, musicians, and filmmakers in Iran continue to draw upon his imagery.

Rumi and Iranian Identity

For many Iranians, Rumi embodies the humanistic and universal dimension of Persian civilization. He is a reminder that Iran’s cultural contributions extend far beyond borders and politics. His life story—beginning in Balkh, journeying through Nishapur, Damascus, and finally Konya—reflects the cosmopolitan nature of Persianate culture, which has historically transcended national boundaries.

At a time when Iran faces isolation in international politics, the memory of Rumi allows Iranians to project a different face to the world: one of spirituality, tolerance, and poetic brilliance. Through him, Iran claims a share of universal heritage.

The Global Rumi Phenomenon

In the West, especially in the United States and Europe, Rumi has become one of the best-selling poets of modern times. Translations—some accurate, others heavily adapted—have introduced millions to his vision. Spiritual movements, yoga groups, and interfaith circles quote his verses to emphasize love and peace.

This global popularity, however, sometimes strips away the explicitly Islamic and Persian context of his poetry. Many Western readers encounter Rumi as a universal mystic without realizing his deep grounding in the Qur’an, Islamic philosophy, and Persian culture. Scholars in Iran often critique these “New Age” interpretations for detaching him from his roots.

Still, even in this simplified form, Rumi’s message of love and transcendence resonates with contemporary seekers. His works bridge East and West, past and present.

Rumi in Interfaith Dialogue

In recent decades, Rumi has also emerged as a symbol of interfaith understanding. His poetry, which praises love as the essence of all religions, is often cited in Christian-Muslim dialogues. His reminder that “the lamps are different, but the light is the same” captures the spirit of unity across traditions.

In Iran, this universal dimension is emphasized in cultural diplomacy. Rumi becomes a soft power ambassador, showcasing Iran’s contribution to global spirituality. Conferences and exhibitions on Rumi have been held jointly with Turkey, Afghanistan, and UNESCO, highlighting his role as a shared cultural heritage figure.

A Legacy of Resilience

Rumi lived in a turbulent age marked by Mongol invasions, political instability, and displacement. Yet, instead of despair, he turned suffering into a source of creativity. This resilience makes him especially relevant today. For Iranians who endure sanctions, economic struggles, and political crises, Rumi’s message is a reminder that the human spirit can transform adversity into growth.

“Don’t get lost in your pain,” he wrote. “Know that one day your pain will become your cure.”

Such verses still console millions, offering hope that hardship may birth wisdom and unity.

Rumi as a Guide for the Future

Ultimately, Rumi’s legacy for Iran and the world lies not just in his poetry but in his vision of human potential. He invites readers to embrace vulnerability, to cultivate love, and to discover divinity within themselves. His teachings are not abstract philosophy but a roadmap for living—through compassion, tolerance, and spiritual courage.

For Iran, Rumi remains a cultural jewel, reminding the nation of its profound role in shaping human civilization. For the world, he is a universal master whose voice echoes across languages and cultures, a mystic who continues to transform strangers into companions on the same journey of the soul.

Among the most defining chapters in Rumi’s life, and indeed in world literature, is his profound and enigmatic bond with Shams al-Din Mohammad Tabrizi (1185–1248). This relationship was not merely a meeting of teacher and pupil but a transformative encounter that redirected the course of Rumi’s spiritual and literary trajectory. Without Shams, there may have been no Masnavi, no Diwan-e Shams, and no legacy of Rumi as we know it today.

The Encounter in Konya

Historical accounts record that on November 30, 1244, in the streets of Konya, Rumi crossed paths with Shams, an itinerant dervish of extraordinary presence. Shams was known for his uncompromising devotion to truth, disregard for worldly acclaim, and insistence on piercing through superficial religiosity to reach the heart of divine love. Some traditions suggest they may have met earlier in Syria, but it was in Konya where their bond was cemented.

The initial meeting is often depicted as a confrontation of spirits. Rumi, already a respected jurist and preacher, was challenged by Shams with radical questions that pierced his scholarly armor. Their conversations, stretching for days, shook Rumi’s intellectual foundations and awakened in him a new dimension of mystical awareness. From this point onward, Rumi’s role shifted from that of a conventional scholar to a poet-mystic whose words would transcend centuries.

Shams as the Catalyst

Shams became both muse and mirror for Rumi, igniting within him the fires of longing and divine intoxication. The “Diwan-e Shams-e Tabrizi” stands as a monumental testament to this relationship, containing thousands of ghazals and quatrains suffused with passion, ecstasy, and metaphysical insight. These poems are not simply literary exercises but records of a soul in transformation, guided by the presence—and eventual absence—of Shams.

The disappearance of Shams in 1248, under circumstances still debated by historians, devastated Rumi. Some say Shams was murdered by jealous disciples; others believe he departed voluntarily, refusing to be tied down. Whatever the truth, his absence became a perpetual presence in Rumi’s heart. In turning his grief into verse, Rumi immortalized Shams not merely as a man but as the embodiment of divine love.

The Masnavi as Continuation

If the Diwan reflects Rumi’s passionate cry, the Masnavi-ye Ma’navi is his sober counsel. After Shams’s departure, Rumi’s disciple Husam al-Din Chalabi encouraged him to channel his wisdom into a structured work. Thus began the composition of the six-volume Masnavi, a comprehensive mystical treatise that uses allegory, parable, and philosophical reflection to explore the human journey toward God. In many ways, the Masnavi represents the distilled essence of what Shams had awakened in Rumi—a sustained exploration of love as the path to divine union.

Universal Themes of Love and Transformation

At the heart of both Rumi’s grief for Shams and his broader mystical outlook lies the transformative power of love. For Rumi, love is not sentimental attachment but the very force that shatters the ego, erodes illusions, and unites the seeker with the divine. The pain of separation from Shams becomes, in his poetry, a metaphor for the soul’s yearning to reunite with its divine source.

This theme resonates universally. Across cultures and faiths, readers and listeners hear in Rumi’s verses an articulation of their deepest longings: the desire to transcend isolation, to find meaning, and to dissolve into something greater than oneself. His metaphors—such as the reed flute mourning its separation from the reed bed—are vivid, accessible, and timeless.

A Legacy Beyond Borders

Rumi passed away on December 17, 1273, in Konya. His funeral drew Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others—each claiming him as their own. This inclusivity reflects the essence of his message: that divine truth transcends dogma and that love unites all paths. His mausoleum in Konya, the Mevlana Museum, remains one of the most visited pilgrimage sites in the world, where the whirling dervishes of the Mevlevi order, founded by Rumi’s followers, continue to perform their ritual dance of remembrance.

Today, Rumi’s words adorn the walls of homes, are recited in interfaith gatherings, quoted in political speeches, set to music, and translated into dozens of languages. In Iran, Turkey, Afghanistan, and beyond, he is celebrated as a cultural icon. In the West, his works are among the most widely read of any poet, ancient or modern.

The Living Voice of Mowlana

The enduring relevance of Rumi lies not merely in his historical stature but in the living quality of his voice. He does not speak as a distant sage but as a companion on the journey of the soul. His counsel is intimate, urging us to shed fear, embrace vulnerability, and plunge into the ocean of love.

For modern seekers—whether investors, scholars, artists, or ordinary readers—Rumi offers a compass that points beyond material success toward inner fulfillment. His invitation is simple yet profound: “Come, whoever you are, wanderer, worshipper, lover of leaving. Ours is not a caravan of despair.”

A Guide for All Ages

In sum, the life and works of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi, known as Rumi or Mowlana, embody the union of intellect and spirit, tradition and innovation, grief and joy. His transformative encounter with Shams birthed a literary and spiritual legacy that continues to shape global consciousness.

Rumi remains not only a Persian poet of the 13th century but a universal master whose words carry timeless wisdom. His legacy challenges us to transcend divisions, embrace love as the path to truth, and see in every human heart the reflection of the divine.

As long as humanity seeks meaning, Rumi’s voice will continue to echo—reminding us that the journey to God begins with the journey inward, and that through love, the finite meets the infinite.

End Article